Table of Contents

ToggleORPHEUS - THE MYTH THAT TRANSCENDS TIME AND SPACE

The Orpheus myth is a story from ancient Greek mythology about a musician and poet named Orpheus who had a great love for his wife Eurydice.

Unfortunately, Eurydice died soon after their wedding from a snake bite. Orpheus was so heartbroken that he decided to go to the Underworld to try to bring her back to life. He used his music and singing to charm the gods and creatures of the Underworld, including Hades, the lord of the dead, and Persephone, his queen.

They agreed to let Orpheus take Eurydice back to the world of the living, but on one condition: he must not look back at her until they reached the surface. Orpheus agreed and began to walk out of the Underworld with Eurydice following behind him. However, as he was about to reach the exit, he could not resist the temptation to look back at his beloved wife. As soon as he did, Eurydice vanished and was pulled back into the Underworld forever.

Orpheus was devastated and wandered around the world playing his sad music until he was killed by a group of wild women who were angry that he ignored their advances. His soul finally reunited with Eurydice in the Underworld, where they could be together for eternity

Jean Cocteau Orphic Trilogy

Jean Cocteau, a multifaceted artist, left an indelible mark on the world of literature, cinema, and visual arts. One of his most notable and captivating creations is the Orpheus Trilogy, a collection of three films that reinvent the ancient Greek myth of Orpheus. Released between 1930 and 1960, these films showcase Cocteau’s unique blend of mythological elements, poetic storytelling, and surreal imagery. In this essay, we will delve into the essence of Jean Cocteau’s Orpheus Trilogy, examining its artistic vision, narrative complexity, and enduring significance.

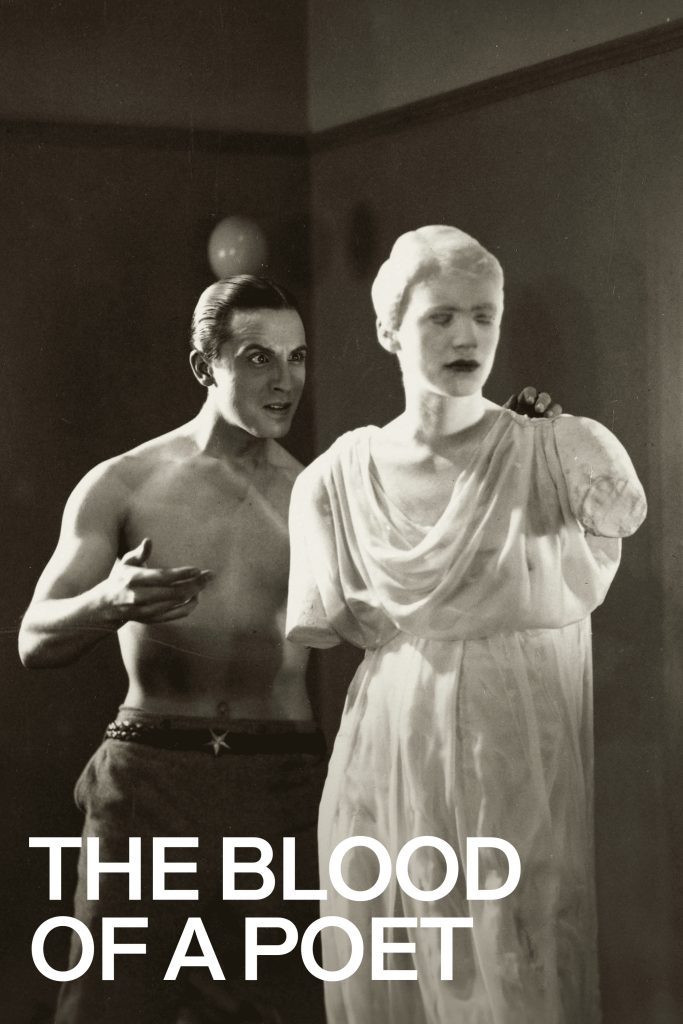

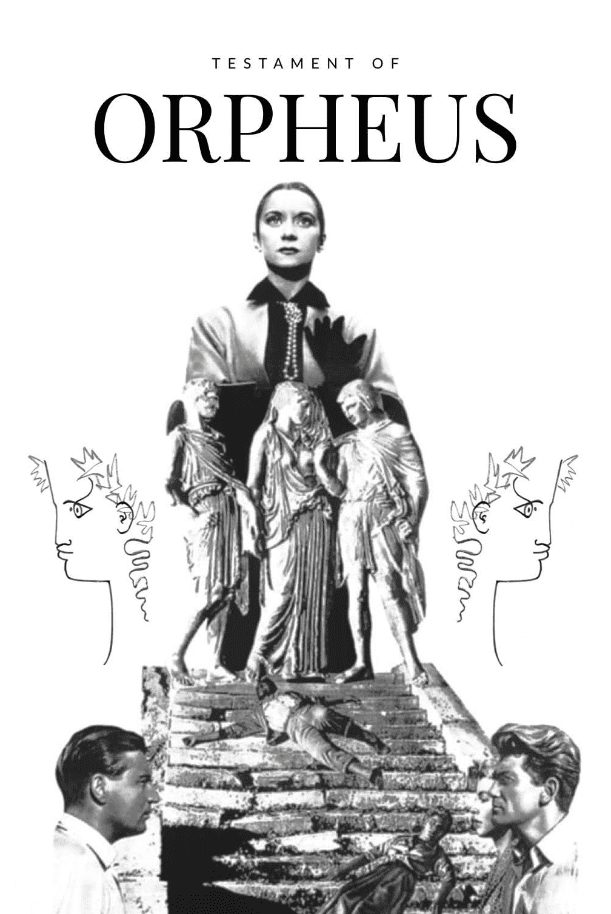

Orphic Theme and Mythological Reinterpretation: The Orpheus Trilogy comprises three films: “The Blood of a Poet” (1930), “Orpheus” (1950), and “The Testament of Orpheus” (1960). At the trilogy’s core lies the mythical figure of Orpheus, the legendary musician-poet whose journey to the Underworld to rescue his beloved Eurydice has been a timeless tale of love, loss, and artistic aspiration. Cocteau, however, revitalizes this ancient myth by intertwining it with modern sensibilities and philosophical reflections.

Surrealistic Imagery and Poetic Storytelling: Cocteau was a prominent figure in the Surrealist movement, and his artistic vision heavily influenced the Orpheus Trilogy. Surrealism aimed to unlock the subconscious mind through dreamlike imagery and unexpected associations, and Cocteau masterfully incorporates these elements into his films. “The Blood of a Poet” sets the tone with its dreamy and abstract sequences, showcasing the battle between the artist’s imagination and reality.

In “Orpheus,” Cocteau presents a unique perspective on the myth, exploring the intertwining of the living and the dead, the mundane and the mystical. This film’s mesmerizing imagery and poetic storytelling elevate the tale of Orpheus and Eurydice into a profound meditation on art, love, and the transcendence of death.

Art as a Transformative Force: Throughout the Orpheus Trilogy, Cocteau portrays art as a transformative force that blurs the boundaries between life and artistry. The poet, Orpheus, becomes a symbol of the artist, and his journey to the Underworld mirrors the artist’s quest for inspiration and the confrontation with mortality. Cocteau’s portrayal of Orpheus as a poet deeply intertwined with the mysteries of life and death highlights the power of art to access the realms beyond the visible world.

Reinventing Classic Characters: In the Orpheus Trilogy, Cocteau reimagines the classic characters of the myth in intriguing and unexpected ways. Orpheus is no longer the traditional heroic figure but a conflicted and flawed artist grappling with his artistic identity. Eurydice, too, undergoes a transformation, becoming a mysterious and enigmatic figure whose true nature remains elusive. By humanizing these mythical characters, Cocteau breathes new life into the timeless narrative.

The Testament of Orpheus: A Cinematic Autobiography: The final installment of the trilogy, “The Testament of Orpheus,” serves as an autobiographical reflection on Cocteau’s life and artistic journey. In this film, Cocteau plays himself, engaging with other artists and historical figures from various epochs. The film blurs the lines between reality and fiction, symbolizing Cocteau’s belief in the interconnectedness of art and life. “The Testament of Orpheus” is a visionary farewell from Cocteau to the world he inhabited, showcasing his profound artistic legacy.

Jean Cocteau’s Orpheus Trilogy is a masterpiece that transcends conventional storytelling and ventures into the realms of myth, art, and the subconscious. Through poetic storytelling, surrealistic imagery, and innovative reinterpretation of classic characters, Cocteau presents a thought-provoking exploration of the artistic process, the power of imagination, and the eternal quest for inspiration. These films remain a testament to Cocteau’s genius and his enduring influence on the realms of literature and cinema. As the trilogy continues to inspire artists and captivate audiences, it solidifies Cocteau’s status as one of the most visionary and imaginative artists of the 20th century.

Jean Cocteau Influence in Cinéma

Jean Cocteau was a multifaceted artist who had a significant influence in French cinema as a director, writer, actor, and theorist. He was one of the pioneers of the avant-garde and surrealist movements, creating films that challenged the conventions of narrative, realism, and representation. He also experimented with various cinematic techniques and devices, such as slow motion, reverse motion, dissolves, superimpositions, mirrors, and voice-overs. He was interested in exploring the themes of poetry, myth, dream, death, love, and identity in his films. Some of his most influential films include:

The Blood of a Poet (1930), his first film and part of his Orphic trilogy. It is a series of four episodes that depict the poet’s journey into his own subconscious and imagination. The film features surreal imagery and symbolism that express Cocteau’s views on art and reality

Beauty and the Beast (1946), his first narrative film and an adaptation of the classic fairy tale. It is a visually stunning film that creates a magical atmosphere with elaborate sets, costumes, makeup, and special effects. The film also explores the themes of transformation, desire, and sacrifice

Orpheus (1950), the second part of his Orphic trilogy and a modern retelling of the Greek myth. It is a film that blends fantasy and reality, using devices such as radios, motorcycles, and mirrors to create a sense of mystery and ambiguity. The film also reflects Cocteau’s own artistic struggles and identity

Cocteau’s influence in French cinema can be seen in the works of many filmmakers who admired him, such as François Truffaut, Jean-Luc Godard, Jacques Demy, Agnès Varda, and Jean-Pierre Jeunet. He was also recognized by international filmmakers such as Federico Fellini, Ingmar Bergman, Luis Buñuel, David Lynch, and Guillermo del TorO

THE BLOOD OF THE POET

The Blood of a Poet is divided into four sections. In section one, an artist sketches a face and is startled when its mouth starts moving. He rubs out the mouth, only to discover that it has transferred to the palm of his hand. After experimenting with the hand for a while and falling asleep, the artist awakens and places the mouth over the mouth of a female statue.

In section two, the statue speaks to the artist, cajoling him into passing through a mirror. The mirror transports the artist to a hotel, where he peers through several keyholes, witnessing such people as an opium smoker and a hermaphrodite. The artist is handed a gun and a disembodied voice instructs him in how to shoot himself in the head. He shoots himself but does not die. The artist cries out that he has seen enough and returns through the mirror. He smashes the statue with a mallet.

In section three, some students are having a snowball fight. An older boy throws a snowball at a younger boy, but the snowball turns out to be a chunk of marble. The young boy dies from the impact.

In the final section, a card shark plays a game with a woman on a table set up over the body of the dead boy. A theatre party looks on. The card shark extracts an Ace of Hearts from the dead boy’s breast pocket. The boy’s guardian angel appears and absorbs the dead boy. He also removes the Ace of Hearts from the card shark’s hand and retreats up a flight of stairs and through a door. Realizing he has lost, the card shark commits suicide as the theatre party applauds. A female player transforms into the formerly smashed statue and walks off through the snow, leaving no footprints. In the film’s final moments the statue is shown with an ox, a globe, and a lyre.

Intercut through the film, oneiric images appear, including spinning wire models of a human head and rotating double-sided masks.

ORPHEUS

Set in contemporary Paris, the story of the film is a variation of the classic Greek myth of Orpheus and Eurydice. The picture begins with Orpheus (Marais), a famous poet, visiting the Café des Poètes. At the same time, a Princess (Casares) and Cégeste (Édouard Dermit), a handsome young poet whom she supports, arrive. The drunken Cégeste starts a brawl. When the police arrive and attempt to take Cégeste into custody, he breaks free and flees, only to be run down by two motorcycle riders. The Princess has the police place Cégeste into her car in order to “transport him to the hospital”. She also orders Orpheus into the car in order to act as a witness. Once in the car, Orpheus discovers Cégeste is dead and that the Princess is not going to the hospital. Instead, they drive to a chateau (the landscape through the car windows is presented in negative) accompanied by the two motorcycle riders as abstract poetry plays on the radio. This takes the form of seemingly meaningless messages, like those broadcast to the French Resistance from London during the Occupation.

At the ruined chateau, the Princess reanimates Cégeste into a zombie-like state, and she, Cégeste, and the two motorcycle riders (the Princess’ henchmen) disappear into a mirror, leaving Orpheus alone. He wakes in a desolate landscape, where he stumbles on the Princess’ chauffeur, Heurtebise (Périer), who has been waiting for Orpheus to arrive. Heurtebise drives Orpheus home where Orpheus’ pregnant wife Eurydice (Déa), a police inspector, and Eurydice’s friend Aglaonice (head of the “League of Women”, and apparently in love with Eurydice) discuss Orpheus’ mysterious disappearance. When Orpheus comes home, he refuses to explain the details of the previous night despite the questions which linger over the fate of Cégeste, whose body cannot be found. Orpheus invites Heurtebise to live in his house and to store the Rolls in Orpheus’ garage, should the Princess return. Eurydice attempts to tell Orpheus that she is with child, but is silenced when he rebuffs her.

While Heurtebise falls in love with Eurydice, Orpheus becomes obsessed with listening to the abstract poetry which only comes through the Rolls’ radio, and it is revealed that the Princess is apparently Death (or one of the suborders of Death). Cocteau himself commented on such interpretation:

“Among the misconceptions which have been written about Orphée, I still see Heurtebise described as an angel and the Princess as Death. In the film, there is no Death and no angel. There can be none. Heurtebise is a young Death serving in one of the numerous sub-orders of Death, and the Princess is no more Death than an air hostess is an angel. I never touch on dogmas. The region that I depict is a border on life, a no man’s land where one hovers between life and death”.

When Eurydice is killed by Death’s henchmen, Heurtebise proposes to lead Orpheus through the Zone (depicted as a ruined city – actually the ruins of Saint-Cyr military academy) into the Underworld in order to reclaim her. Orpheus reveals that he may have fallen in love with Death who has visited him in his dreams. Heurtebise asks Orpheus which woman he will betray: Death or Eurydice. Orpheus enters the afterlife by donning a pair of surgical gloves left behind by the Princess after Eurydice’s death.

In the Underworld, Orpheus finds himself as a plaintiff before a tribunal which interrogates all parties involved in the death of Eurydice. The tribunal declares that Death has illegally claimed Eurydice, and they return Eurydice to life, with one condition: Orpheus may not look upon her for the rest of his life on pain of losing her again. Orpheus agrees and returns home with Eurydice. They are accompanied by Heurtebise, who has been assigned by the tribunal to assist the couple in adapting to their new, restrictive life together.

Eurydice visits the garage where Orpheus constantly listens to the Rolls’ radio in search of the unknown poetry. She sits in the backseat. When Orpheus glances at her in the mirror, Eurydice disappears. A mob from the Café des Poètes (stirred to action by Aglaonice) arrives in order to extract vengeance from Orpheus for what they suppose to be his part in the murder of Cégeste. Orpheus confronts them, armed with a pistol given to him by Heurtebise, but he is disarmed and shot. Orpheus dies and finds himself in the Underworld. This time, he declares his love to Death who has decided to herself die in order that he might become an “immortal poet”. The tribunal this time sends Orpheus and Eurydice back to the living world with no memories of the previous events. Orpheus learns that he is to be a father, and his life begins anew. Death and Heurtebise, meanwhile, walk through the ruins of the Underworld toward an even worse fate than death—to become judges themselves.

THE TESTAMENT OF ORPHEUS

Testament of Orpheus (French: Le testament d’Orphée) is a 1960 black-and-white film with a few seconds of color film spliced into it. Directed by and starring Jean Cocteau, who plays himself as an 18th-century poet, the film includes cameo appearances by Pablo Picasso, Jean Marais, Charles Aznavour, Jean-Pierre Leaud, and Yul Brynner. It is considered the final part of The Orphic Trilogy, following The Blood of a Poet (1930) and Orphée (1950).

One critic described it as a “wry, self-conscious re-examination of a lifetime’s obsessions” with Cocteau placing himself at the center of the mythological and fictional world he spun throughout his books, films, plays and paintings. The film includes numerous instances of “double takes”, including one scene where Cocteau, walking past himself, looks back to see himself in what was described by one scholar as “a retrospective on the Cocteau œuvre”.

The New York Times called it “self-serving”, noting that the pretension of the film was certainly intended by Cocteau as his last statement made on film: “as much a long-winded self-analysis as an extraordinary succession of visually arresting images”.

Picasso had introduced Cocteau to the photographer Lucien Clergue who was brought in to photo-document the film’s production. His black-and-white stills were published in 2001 as Jean Cocteau and The Testament of Orpheus.

Other Versions of Orpheus

There are many modern adaptations of the Orpheus myth in various forms of art and media. Some of the best well known examples include:

Black Orpheus (1959) is a Brazilian film that retells the story of Orpheus and Eurydice in the context of the Carnival in Rio de Janeiro. The film won the Academy Award for Best Foreign Language Film and the Palme d’Or at the Cannes Film Festival 1.

Hadestown (2016) is a musical based on a concept album by Anaïs Mitchell. It sets the story of Orpheus and Eurydice in a post-apocalyptic world where Hades is a ruthless industrialist who rules over an underground city. The musical won eight Tony Awards, including Best Musical 2.

The Sandman (1989-1996) is a comic book series by Neil Gaiman that features Orpheus as a recurring character. He is the son of Morpheus, the god of dreams, and Calliope, one of the Muses. He appears in several stories, such as “The Song of Orpheus” and “Brief Lives”, where he plays a role in the events of the Endless family 3.

Orfeo ed Euridice (1762) is an opera by Christoph Willibald Gluck that is considered one of the most influential works of the classical period. It simplifies the plot and focuses on the emotions of the characters, using music to express their feelings. It also introduces a happy ending where Orpheus succeeds in bringing Eurydice back to life with the help of Amor, the god of love 4.

Orpheus Descending (1957) is a play by Tennessee Williams that is a modern version of the Orpheus myth. It tells the story of Val Xavier, a young musician who arrives in a small town in Mississippi and falls in love with Lady Torrance, a married woman who is unhappy with her abusive husband. Their affair leads to tragedy and violence